Sigmund Freud (1856-1939), an Austrian neurologist, is widely recognized as the founding father of psychoanalysis. Freud exploration of the unconscious, through techniques like dream analysis and free association, was groundbreaking. Freud proposed that the mind comprises three distinct parts: the id, ego, and superego. This is called theory of mind or Psychoanalysis. These elements interact to shape human behavior and personality. Freud’s theories, including the Oedipus complex and the concept of repression, have been both influential and controversial. His work laid the foundation for modern psychology and psychotherapy.

In this article, we will explore his theory of mind. Freud’s insights offer a unique perspective on human behavior, emphasizing the profound influence of unconscious processes. We’ll explore the dynamics of the id, ego, and superego, unraveling how these components interact. Additionally, we’ll examine key concepts like dream interpretation and the significance of childhood experiences in shaping the adult psyche. Freud’s theory, though debated, provides a compelling framework for understanding the complexities of the human mind.

Freud’s Theory of Mind

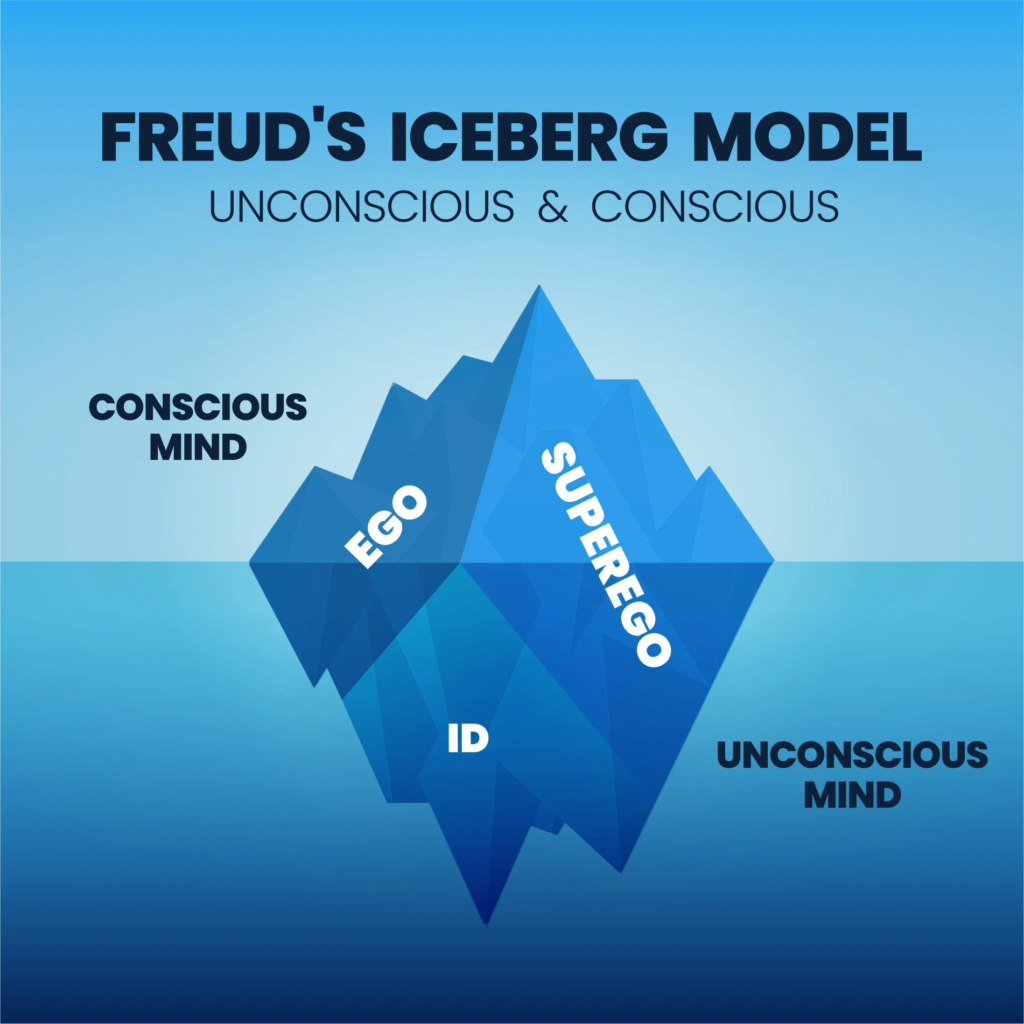

According to Freudian theory, the human mind is divided into two primary components: the conscious and unconscious mind. Let’s delve into the realm of the conscious mind, where we explore the things that we are fully aware of or can effortlessly bring to the forefront of our thoughts. The unconscious mind, in contrast, encompasses all the elements that lie beyond our conscious awareness. These include our hidden wishes, desires, hopes, urges, and memories, which silently shape our behavior.

In Freudian psychology, the mind is often likened to an iceberg. Think of the visible tip of an iceberg as only a small fraction of the mind, while the vast expanse of ice beneath the water symbolizes the expansive unconscious.

It is worth noting that the origin of the iceberg metaphor is a subject of debate among scholars. Some researchers argue that there is no evidence of Freud mentioning an iceberg in his writings, raising questions about its true source (Green, 2019).

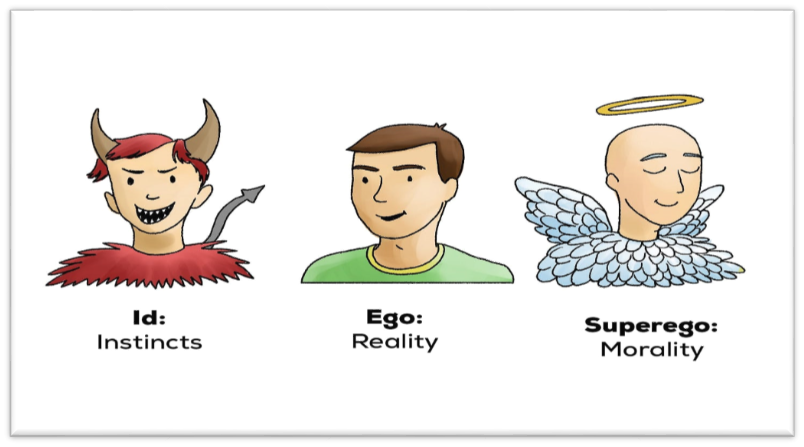

Furthermore, apart from these two fundamental aspects of the mind, Freudian theory also categorizes human personality into three primary components: the id, ego, and superego.

Each component contributes uniquely to one’s personality and interacts significantly, influencing individuals. These elements of character develop at different stages of life. According to Freud’s theory, some parts of your personality are more primal and may push you to act on your basic desires, while other parts aim to counteract these urges and make you conform to the demands of reality. Let’s delve deeper into these crucial personality components, understanding how they function individually and interact with one another.

ID:

According to Freud, the id is the source of all psychic energy, making it the primary component of personality.

- The id is the only component of personality that is present from birth.

- This aspect of personality is entirely unconscious and includes instinctive and primitive behaviors.

- The id is driven by the pleasure principle, which strives for immediate gratification of all desires, wants, and needs.

When these needs aren’t met right away, it causes anxiety or tension. For instance, if you’re hungry or thirsty, you’ll naturally try to eat or drink immediately.

The id plays a crucial role early in life by ensuring infants’ needs are fulfilled. If a baby is hungry or uncomfortable, they cry until their id-driven demands are satisfied. In infancy, the id ultimately governs their behavior, and reasoning with them isn’t practical when these needs require satisfaction.

ID Example

Imagine trying to make a baby wait until lunchtime to eat. The baby’s id wants instant satisfaction, and since the other aspects of their personality aren’t developed yet, the baby cries until their needs are met.

However, always giving in to these desires isn’t practical or possible. If we were solely guided by the pleasure principle, we might grab things from others to fulfil our cravings, which would disrupt and be socially unacceptable behaviour. Freud suggests that the id deals with the tension from the pleasure principle by using primary process thinking, creating a mental image of what it desires to satisfy its needs. (Boag”Ego, Drives, and the Dynamics of Internal Objects”)

The Ego:

- Freud believed that the ego emerges from the id and serves to channel the id’s impulses in a socially acceptable way.

- The ego operates in the mind’s conscious, preconscious, and unconscious realms.

- Its primary role is to handle real-world situations and navigate the demands of reality.

Everyone possesses an ego, but it’s distinct from your overall personality. The ego functions based on the reality principle, aiming to satisfy the id’s desires in practical and socially acceptable ways. It evaluates the pros and cons of actions before deciding whether to act on impulses or let them go.

While people may casually use the term “ego” to imply someone’s inflated self-importance, the ego has a positive role in the realm of personality. It keeps you grounded in reality and prevents the id and superego from pulling you too far toward your basic urges or moral virtues. A strong ego reflects a strong self-awareness.

Freud likened the id to a horse and the ego to its rider. The horse provides power and movement while the rider offers guidance and direction. Without the rider, the horse would wander aimlessly and act as it pleases. The rider directs the horse to reach its desired destination.

Additionally, the ego manages tension from unmet impulses through secondary process thinking. It attempts to find a real-world object that matches the mental image created by the id’s primary process.

The Ego Example

Imagine being in a lengthy work meeting where your hunger grows. While the id might want you to impulsively get up and grab a snack, the ego advises you to stay seated and wait.

Rather than acting on the id’s urges, you spend the meeting thinking about eating a cheeseburger. After the meeting, you can find and eat that cheeseburger to satisfy your id’s demands practically and suitably.

The Superego:

The final part of the personality to develop is the superego.

- According to Freud, the superego starts emerging around age five.

- It contains our internalized moral values and ideals, which we learn from our parents and society, shaping our sense of right and wrong.

- The superego offers guidelines for making judgments.

It consists of two parts:

The conscience holds information about behaviors deemed harmful by parents and society, often leading to punishments, consequences, or feelings of guilt and remorse.

The ego ideal includes the rules and standards of behavior that the ego aspires to follow.

The superego works to refine and civilize our behavior, restraining unacceptable id impulses and pushing the ego to adhere to idealistic standards rather than purely realistic ones. It operates in the conscious, preconscious, and unconscious mind.

Superego Example

The superego comes into play when you act on id urges, making you feel guilty or ashamed. It can also make you feel good when you resist primal urges.

Other examples of the superego include:

- A woman resists the urge to steal office supplies because her superego tells her it’s wrong.

- A man realizes he wasn’t charged for an item at the store and returns to pay because his internal sense of right and wrong compels him.

- A student considers cheating on a test but decides not to because they know it’s morally wrong, even though they think they won’t get caught.

The Interaction of the Id, Ego, and Superego:

When discussing the id, ego, and superego, it’s crucial to understand that they are not distinct entities with fixed boundaries. These elements continuously interact and influence an individual’s personality and actions.

Given these competing forces, conflicts can arise among the id, ego, and superego. Freud introduced the “ego strength” concept to describe the ego’s capacity to function amid these conflicting influences.

Someone with solid ego strength can skillfully handle these pressures, whereas an individual with excessive or insufficient ego strength may become inflexible or disruptive.

What happens if there’s an imbalance, according to Freud?

Freud believed a healthy personality results from a balanced interaction between the id, ego, and superego. When the ego effectively moderates between the demands of reality, the id, and the superego, it fosters a healthy and well-adjusted personality.

However, if there’s an imbalance among these elements, it can lead to maladaptive personality traits. For instance, someone with an overly dominant id might become impulsive and uncontrollable or even engage in criminal behavior, disregarding whether their actions are appropriate or legal.

On the other hand, an excessively dominant superego could lead to an overly moralistic and judgmental personality. Such a person might struggle to accept anything or anyone they perceive as “bad” or “immoral.”

Bibliography

“A New Conceptualization of the Conscience.” Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 9, 8 Oct. 2018, www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01863/full, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01863.Bibliography:

“Ego, Drives, and the Dynamics of Internal Objects.” Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 5, no. 666, 1 July 2014, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4076885/, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00666.

Bargh, John A., and Ezequiel Morsella. “The Unconscious Mind.” Perspectives on Psychological Science, vol. 3, no. 1, Jan. 2008, pp. 73–79, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2440575/, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6916.2008.00064.x.

Boag, Simon. “Ego, Drives, and the Dynamics of Internal Objects.” Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 5, no. 666, 1 July 2014, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4076885/, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00666.

Carhart-Harris, R. L., and K. J. Friston. “The Default-Mode, Ego-Functions and Free-Energy: A Neurobiological Account of Freudian Ideas.” Brain, vol. 133, no. 4, 28 Feb. 2010, pp. 1265–1283, https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awq010.

Churchill, Rachel, et al. “Psychodynamic Therapies versus Other Psychological Therapies for Depression.” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 8 Sept. 2010, https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd008706.

Grzybowski, Andrzej, and Joanna Żołnierz. “Sigmund Freud (1856–1939).” Journal of Neurology, vol. 268, no. 6, 8 June 2020, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-020-09972-4.

Kovačić Petrović, Zrnka, et al. “Comparison of Ego Strength between Aggressive and Non-Aggressive Alcoholics: A Cross-Sectional Study.” Croatian Medical Journal, vol. 59, no. 4, Aug. 2018, pp. 156–164, https://doi.org/10.3325/cmj.2018.59.156. Accessed 22 Oct. 2020.

Pulcu, Erdem. “An Evolutionary Perspective on Gradual Formation of Superego in the Primal Horde.” Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 5, 2014, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00008.

Schalkwijk, Frans. “A New Conceptualization of the Conscience.” Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 9, 8 Oct. 2018, www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01863/full, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01863.

Pingback: Freud's concept of Cathexis and Anticathexis

Pingback: Let’s find out some Famous Psychologists and their Theories - KnownPsychology

Pingback: Freud’s explain Hysteria _ this is a problem of mind

Pingback: Freud theory of Repression _ the unconscious mind

Pingback: Psychoanalysis: The concept of Talk Therapy by Freud

Pingback: Sigmund Freud: A Biography of the Father of Psychoanalysis -

Pingback: How Therapy Works? The Power of Self-Reflection and Healing